|

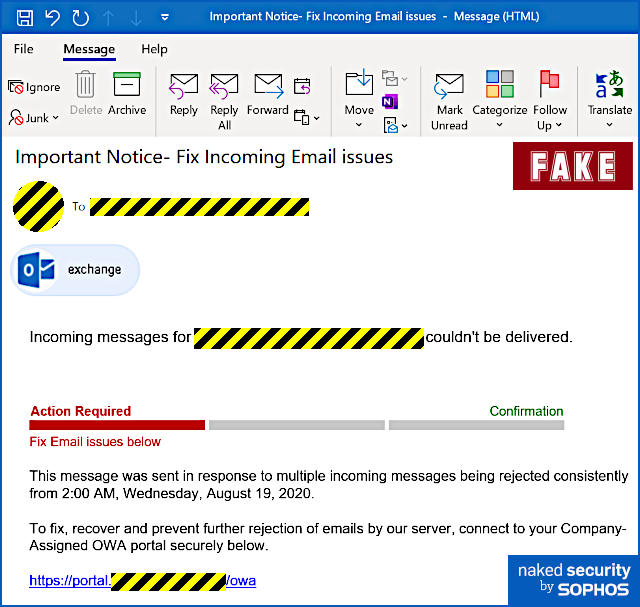

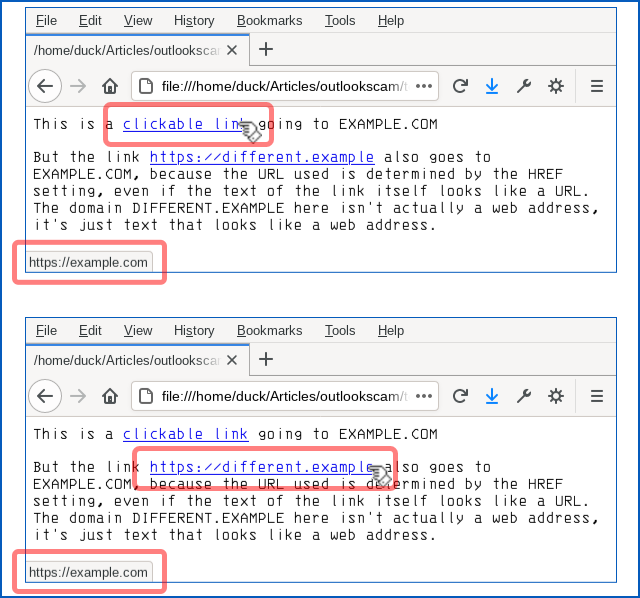

Apart from some slightly clumsy wording (but when was the last time you received an email about a technical matter that was plainly written in perfect English?) and a tiny error of grammar, we thought it was surprisingly believable and worth writing up on that account, to remind you how modern phishers are presenting themselves. Yes, you ought to be suspicious of emails like this. No, you shouldn’t click through even out of interest. No, should never enter your email password in circumstances like this. But the low-key style of this particular scam caught our eye, making it the sort of message that even a well-informed user might fall for, especially at the end of a busy day, or at the very start of the day after. Here’s how it arrives – note that in the sample we examined here, the crooks had rigged up the email content so that it seemed to be an automated message from the recipient’s own account, which fits with the theme of an automatic delivery error: Incoming messages for [REDACTED] couldn’t be delivered. This message was sent in response to multiple incoming messages being rejected consistently from 2:00 AM, Wednesday, August 19, 2020. To fix, recover and prevent further rejection of emails by our server, connect to your Company-Assigned OWA portal securely below. Only if you were to dig into the email headers would it be obvious that this message actually arrived from outside and was not generated automatically by your own email system at all. The clickable link is perfectly believable, because the part we’ve redacted above (between the text https://portal and the trailing /owa, short for Outlook Web App) will be your company’s own domain name. But even though the blue text of the link itself looks like a URL, it isn’t actually the URL that you will visit if you click it. Remember that a link in a web page consists of two parts: first, the text that is highlighted, usually in blue, which is clickable; second, the destination, or HREF (short for hypertext reference), where you actually go if you click the blue text. A link is denoted in HTML by an ANCHOR tag that appears between the markers <A> and </A> while the destination web address is denoted by an HREF attribute inside the opening anchor tag delimiter. Like this: This is a <A HREF='https://example.com'>clickable link</A> going to EXAMPLE.COM

But the link <A HREF='https://example.com'>https://different.example</A> also

goes to EXAMPLE.COM, because the URL used is determined by the HREF setting,

even if the text of the link itself looks like a URL. The domain DIFFERENT.EXAMPLE

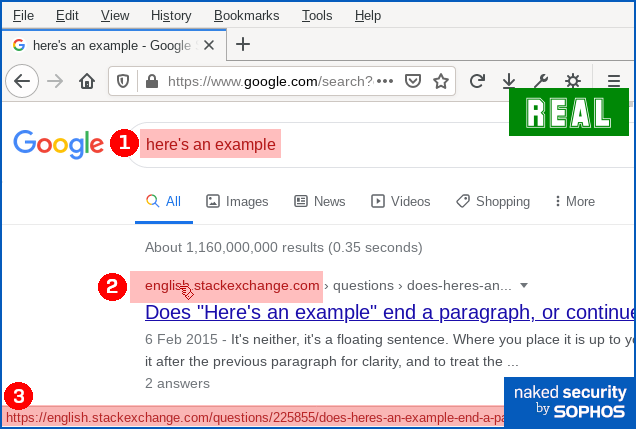

here isn't actually a web address, it's just text that looks like a web address. Why not just block links that look deceptive? If you’re thinking that “links that deliberately look as though they go somewhere else” sound suspicious, you’d be right. You might wonder why browsers, operating systems and cybersecurity products don’t automatically detect and block this kind of trick, where there’s an obvious and deliberate mismatch between the clickable text and the link it takes you to. Unfortunately, even mainstream sites use this approach, making it effectively impossible to rely up front on what a link looks like, or even where it claims to go in your browser, in order to work out exactly where your network traffic will go next. For instance, here’s a Google search for here's an example: You can see that if you ① search for here's an example, you’ll receive a answer in which ② an explicit domain name (in this case, english.stackexchange.com) is used as the visible text of a clickable link. You can also see that when you hover over the domain name link, you’ll see ③ a full URL that apparently confirms that clicking the link will take you to the named site. However, if you use Firefox’s Copy Link Location option to recover the ultimate link, you’ll see – thanks to the magic of JavaScript – that your web request actually goes to a URL of this sort: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&

cad=rja&uact=8&ved=[REDACTED]&

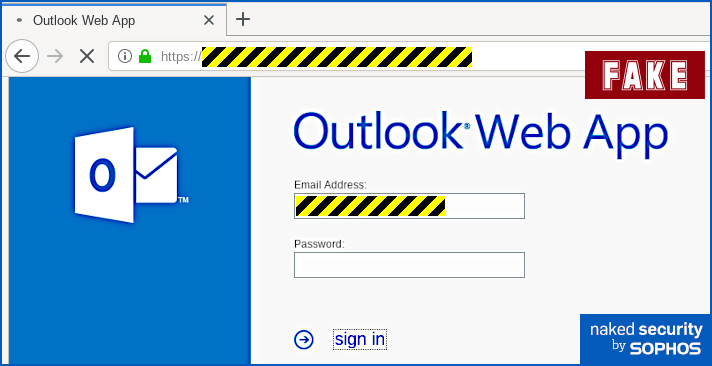

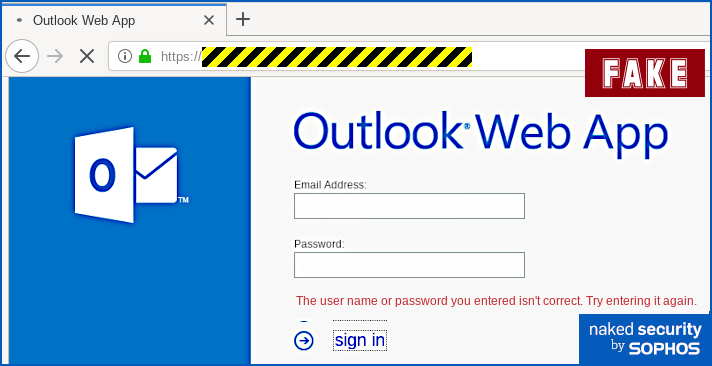

url=https%3A%2F%2Fenglish.stackexchange.com%2Fquestions%2F225855%2Fheres-an-example[...] Eventually, you will end up at the URL shown at position ③ in the screenshot above, but you’ll be redirected (quickly enough that you might not notice) via a Google track-and-redirect link first. So you do end up where the browser told you, but not quite as explicitly and directly as you might have expected – you get there indirectly via Google’s own advertising network. What happens next? The good news is that in the case of this phish you will see the actual web page you’ll be taken to if you hover your cursor over the link-that-looks-like-a-different-link. That’s because email clients and webmail systems generally don’t allow JavaScript to run, given that emails could have come from anywhere – even if they say they came from your own account, as this one does. So you ought to spot this phish easily if you stop to check where the link-that-looks-internal really ends up. In our case (note that the exact URL and server name may vary every time), the real link did not go to https://portal.[REDACTED]/owa, as suggested by the text of the link. Instead, it went to a temporary Microsoft Azure cloud web storage URL, as shown below, which clearly isn’t the innocent-looking URL implied in the email: The phishing page If you do click through, and your endpoint or firewall filter doesn’t block the request, you will see a phishing page that we must grudgingly admit is elegantly simple: Your email address is embedded in the link in the email that you click on, so the phishing page can fill in the email field as you would probably expect. When we tried this page, deliberately putting in fake data, we received an error message after the first attempt, as though we’d made a mistake typing in the password: No matter what we did the second time, we achieved “success”, and moved onwards in the scam. How it ends One tricky problem for phishing crooks is what to do at the end, so you don't belatedly realise it's a scam and rush off to change your password (or cancel your credit card, or whatever it might be). In theory, they could try using the credentials you just typed in to login for you and then dump you into your real account, but there's a lot that could go wrong. The crooks almost certainly will test out your newly-phished password pretty soon, but probably not right away while you are paying attention and might spot any anomalies that their attempted login might cause. They could just put up a "thanks, you may now continue normally" page, and often that's exactly what they do as a simple way to sign off their scam. Or they find a page that's related to the account they were phishing for, and redirect you there. This leaves you on a web page that really does have a genuine URL in the address bar – what's often called a decoy page because it leads you out at the end of the scam with your innocence intact. That’s what happened here – it’s not perhaps exactly the page you might expect, but it’s believable enough because it leaves you on a genuine Outlook-related web page with a genuine Microsoft URL: What to do?

Thanks:

Paul Ducklin, Sophos.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2023

|

|

2951 Britannia crescent

Port Coquitlam BC, V3B 4V5 778-776-6222 Hours of operation Mon - Fri 9 a.m. - 6 p.m. Sat 11 a.m. - 5 p.m. (by appointment only) Sunday & Holidays - Closed |

Business Number 778569517BC0001 - © Copyright CompuBC, All Rights Reserved.

|