|

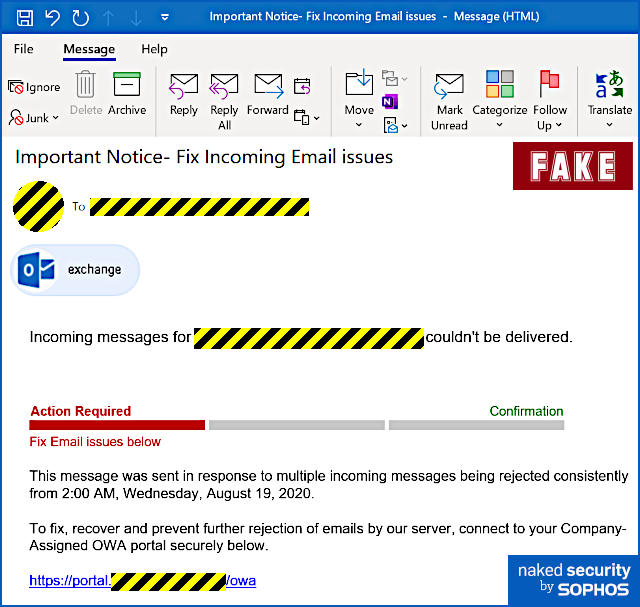

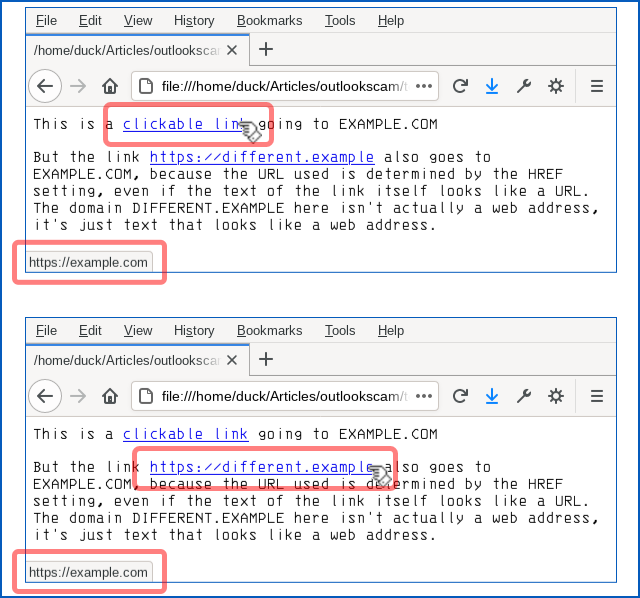

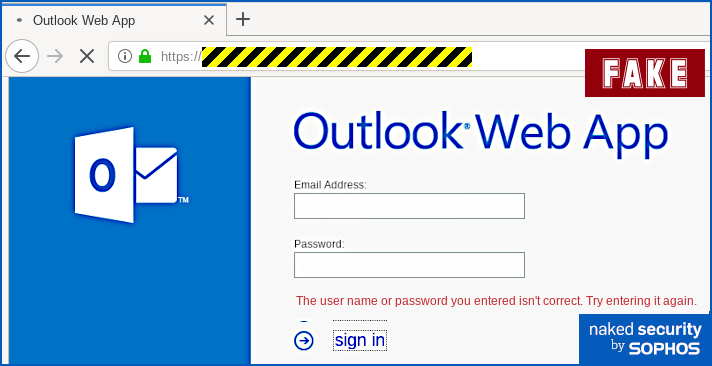

Apart from some slightly clumsy wording (but when was the last time you received an email about a technical matter that was plainly written in perfect English?) and a tiny error of grammar, we thought it was surprisingly believable and worth writing up on that account, to remind you how modern phishers are presenting themselves. Yes, you ought to be suspicious of emails like this. No, you shouldn’t click through even out of interest. No, should never enter your email password in circumstances like this. But the low-key style of this particular scam caught our eye, making it the sort of message that even a well-informed user might fall for, especially at the end of a busy day, or at the very start of the day after. Here’s how it arrives – note that in the sample we examined here, the crooks had rigged up the email content so that it seemed to be an automated message from the recipient’s own account, which fits with the theme of an automatic delivery error: Incoming messages for [REDACTED] couldn’t be delivered. This message was sent in response to multiple incoming messages being rejected consistently from 2:00 AM, Wednesday, August 19, 2020. To fix, recover and prevent further rejection of emails by our server, connect to your Company-Assigned OWA portal securely below. Only if you were to dig into the email headers would it be obvious that this message actually arrived from outside and was not generated automatically by your own email system at all. The clickable link is perfectly believable, because the part we’ve redacted above (between the text https://portal and the trailing /owa, short for Outlook Web App) will be your company’s own domain name. But even though the blue text of the link itself looks like a URL, it isn’t actually the URL that you will visit if you click it. Remember that a link in a web page consists of two parts: first, the text that is highlighted, usually in blue, which is clickable; second, the destination, or HREF (short for hypertext reference), where you actually go if you click the blue text. A link is denoted in HTML by an ANCHOR tag that appears between the markers <A> and </A> while the destination web address is denoted by an HREF attribute inside the opening anchor tag delimiter. Like this: This is a <A HREF='https://example.com'>clickable link</A> going to EXAMPLE.COM

But the link <A HREF='https://example.com'>https://different.example</A> also

goes to EXAMPLE.COM, because the URL used is determined by the HREF setting,

even if the text of the link itself looks like a URL. The domain DIFFERENT.EXAMPLE

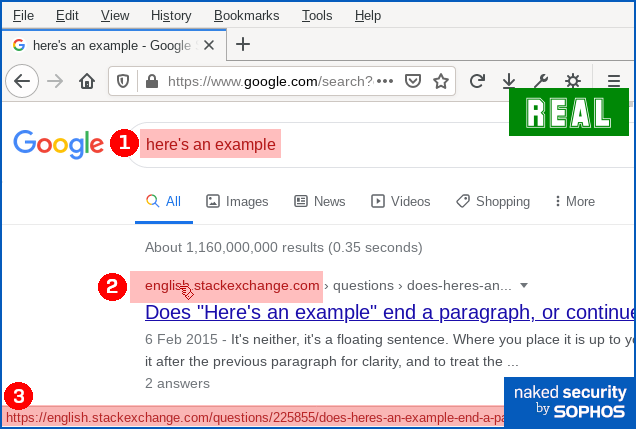

here isn't actually a web address, it's just text that looks like a web address. Why not just block links that look deceptive? If you’re thinking that “links that deliberately look as though they go somewhere else” sound suspicious, you’d be right. You might wonder why browsers, operating systems and cybersecurity products don’t automatically detect and block this kind of trick, where there’s an obvious and deliberate mismatch between the clickable text and the link it takes you to. Unfortunately, even mainstream sites use this approach, making it effectively impossible to rely up front on what a link looks like, or even where it claims to go in your browser, in order to work out exactly where your network traffic will go next. For instance, here’s a Google search for here's an example: You can see that if you ① search for here's an example, you’ll receive a answer in which ② an explicit domain name (in this case, english.stackexchange.com) is used as the visible text of a clickable link. You can also see that when you hover over the domain name link, you’ll see ③ a full URL that apparently confirms that clicking the link will take you to the named site. However, if you use Firefox’s Copy Link Location option to recover the ultimate link, you’ll see – thanks to the magic of JavaScript – that your web request actually goes to a URL of this sort: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&

cad=rja&uact=8&ved=[REDACTED]&

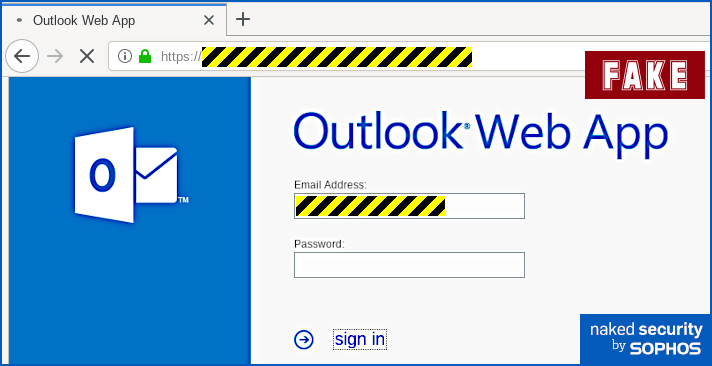

url=https%3A%2F%2Fenglish.stackexchange.com%2Fquestions%2F225855%2Fheres-an-example[...] Eventually, you will end up at the URL shown at position ③ in the screenshot above, but you’ll be redirected (quickly enough that you might not notice) via a Google track-and-redirect link first. So you do end up where the browser told you, but not quite as explicitly and directly as you might have expected – you get there indirectly via Google’s own advertising network. What happens next? The good news is that in the case of this phish you will see the actual web page you’ll be taken to if you hover your cursor over the link-that-looks-like-a-different-link. That’s because email clients and webmail systems generally don’t allow JavaScript to run, given that emails could have come from anywhere – even if they say they came from your own account, as this one does. So you ought to spot this phish easily if you stop to check where the link-that-looks-internal really ends up. In our case (note that the exact URL and server name may vary every time), the real link did not go to https://portal.[REDACTED]/owa, as suggested by the text of the link. Instead, it went to a temporary Microsoft Azure cloud web storage URL, as shown below, which clearly isn’t the innocent-looking URL implied in the email: The phishing page If you do click through, and your endpoint or firewall filter doesn’t block the request, you will see a phishing page that we must grudgingly admit is elegantly simple: Your email address is embedded in the link in the email that you click on, so the phishing page can fill in the email field as you would probably expect. When we tried this page, deliberately putting in fake data, we received an error message after the first attempt, as though we’d made a mistake typing in the password: No matter what we did the second time, we achieved “success”, and moved onwards in the scam. How it ends One tricky problem for phishing crooks is what to do at the end, so you don't belatedly realise it's a scam and rush off to change your password (or cancel your credit card, or whatever it might be). In theory, they could try using the credentials you just typed in to login for you and then dump you into your real account, but there's a lot that could go wrong. The crooks almost certainly will test out your newly-phished password pretty soon, but probably not right away while you are paying attention and might spot any anomalies that their attempted login might cause. They could just put up a "thanks, you may now continue normally" page, and often that's exactly what they do as a simple way to sign off their scam. Or they find a page that's related to the account they were phishing for, and redirect you there. This leaves you on a web page that really does have a genuine URL in the address bar – what's often called a decoy page because it leads you out at the end of the scam with your innocence intact. That’s what happened here – it’s not perhaps exactly the page you might expect, but it’s believable enough because it leaves you on a genuine Outlook-related web page with a genuine Microsoft URL: What to do?

Thanks:

Paul Ducklin, Sophos.

0 Comments

Gone are the days when the internet felt novel: AOL Instant messenger opened up a new way of communicating; Google searches yielded new info at mindblowingly quick speeds; a shared computer in a common space was the norm. We lived and learned through our amateur mistakes—getting hacked, fallings for phishing scams, using our first names and birthdays as passwords.

For younger generations who’ve grown up with technology and social media, the internet has always been ubiquitous. They carry it in their pockets, and use it to stay chronically connected to friends and to navigate everyday life and learning. Is security at the forefront of their minds, or is it something they take for granted? Essentially, are they doomed to repeat our mistakes? Now that many schools are operating virtually, it’s the perfect time to evaluate your kids’ understanding and awareness of digital privacy, and brush up on your own knowledge so that you can be a good guide. Here are CompuBC's tips for encouraging good cybersecurity habits in kids. Instill confidence, not fear The internet can be murky, but we can’t expect kids to avoid it. Rather than talking about the internet like it’s the boogeyman, arm your kids with the knowledge they need to navigate safely: Passwords Just like you’d stress the importance of keeping an ATM Pin secure, remind them that login info and passwords are for their eyes only. Teach good password creation habits. Downloads Make sure they check with you before downloading apps (you can also set parental controls on an iPhone or Apple Device to prevent downloads and purchases from the App Store). For Android, Google offers a Family Link app that allows you to pair your device with your kids’, manage their app downloads, and set limits on screen time. Websites and WiFi Teach them how to identify a secure WiFi network. The simplest rule: if you click on a network and it asks for either a WPA or WPA2 password, you know it’s secure. Both types of passwords are keys for accessing a secured Wifi network; the latter is a more recent version that uses AES (advanced encryption standard) encryption for maximum security. They’ll also want to make sure that websites start with “https” (the ‘s’ here means secure). Limit their access to specific web content using parental controls, which you can set up on their Apple and Android devices. Preach Healthy Skepticism A year-long Stanford study concluded that most school-age children have a hard time differentiating between articles and sponsored content, and possess a general lack of skepticism when it comes to what they read online. Advertisers and content creators are adept at getting users to click and explore ads, apps, games, and articles—just think how likely you are to let curiosity get the best of you when presented with targeted ads. It’s important to encourage kids to think critically about the information they’re presented with online, and to be critical thinkers when navigating the internet. Teach kids about the permanence of shared info online A good golden rule: if you can’t share it with your parents, it’s probably not something you want to put online. There’s certainly a tendency to overshare on social media, and the consequences can range from sheer regret to jeopardizing kids’ safety. Remind your kids that what they put online, even in private channels, stays online, and can be found if someone really wants to find it. Depending on their age, it’s a good idea to monitor their social media accounts, and tell them to keep their accounts private and avoid friending anyone they don’t know in real life. Schedule a check-in with them and scope out their requests and DMs to rid them of bots and scammers. Don’t go it alone—use schools and other learning tools as resources Many schools have their own policies when it comes to using personal devices at school. Talk to your child’s school to find out their rules, and to see if they teach students “digital literacy”—seeing media through a critical lens. Resources like Common Sense offer courses for empowering students in their digital lives, helping them become more adept at navigating the internet. Practice what you preach Familiarize yourself with good cybersecurity habits, from understanding the trail you leave online to quickly improving your online security. Be a resource should they come to you for advice. Set good examples when using your devices, such as not texting while you drive, and being mindful of your own screen time, as kids are likely to pick up on these habits. Likewise, underscore the importance of keeping track of your devices and making sure they are password-protected. Every week or so, news of yet another company’s data breach breaks. Often, the news stories will include a list of what data was or wasn’t compromised: emails, credit card numbers, addresses, etc.

So, you might assume that if a news story doesn’t include “passwords” on the list of compromised data after a breach, there’s no rush to go reset yours. But actually, resetting your password for any compromised account, regardless of whether that password was exposed, is exactly what you should do. Why you should update your password for any compromised account Even though 91% of people know that reusing passwords across accounts is bad, 59% of people still reuse their passwords—even between personal and work accounts. There’s a chance the password you’re using on a compromised account is also being used elsewhere. And if someone already has your email address or other personal information from one breach, and then gets your reused password through another, they can put two and two together to hack your accounts. It’s also possible that the breadth or depth of a breach may not be apparent or reported until months later, so passwords may indeed have been involved. Why take the risk? The bottom line: No matter the extent of a company’s data breach, you should go change that password ASAP. Here are a few more tips for creating strong passwords, and other smart password practices

Questions regarding the use of "anti-virus" or similarly categorized "Internet security" products frequently arise on this site. Many of them are from new Mac users whose previous computer experience was limited to traditionally virus-prone Windows PCs. Early Microsoft Windows versions were notoriously vulnerable to unauthorized modifications and malicious interference, which gave rise to a cottage industry of "anti-virus" software companies responding to a need for the operating system security Microsoft neglected to provide.

Apple and Microsoft's respective operating systems were originally conceived and developed completely separately, for use with completely different hardware, and their evolution has only diverged since their inception. In recent years Microsoft has made great strides in protecting its Windows operating system, but owing to macOS's original concept as a multi-user, multitasking operating system incorporating a fundamental requirement to keep users separate from one another, it was never as vulnerable to begin with. With each new release, macOS has only grown more secure from unauthorized tampering. It's important to understand the nature of threats that exist today, and to appreciate the fact that "anti-virus" software peddlers have been reduced to abject panic as their traditional Windows PC market suffers its inevitable decline. The cottage industry described in the first paragraph has since grown to a multi-billion dollar behemoth with entrenched interests—an enormous beast that demands to be fed. The PC market's demise has led to a predictable response from them and shills who represent their interests, asserting that since Macs are rapidly growing in popularity, they have become just as vulnerable to "viruses" as PCs, implying an even greater need for the products they sell. It just isn't so. What is true is that the growing base of Mac users are being increasingly targeted and exploited for scams that seek to defraud them of their hard-earned money. Criminals who seek to do that cannot succeed without your help. Don't give them the satisfaction. The following describes simple principles that will serve to protect your Mac, and yourself, from the various threats that exist today. It's long, but if you read nothing else, read the first three numbered points and the Summary at the end. They are equally applicable to Macs, PCs, mobile devices or anything else that uses software to communicate with the world beyond it. There will always be threats to your information security associated with using any Internet - connected communications tool:

macOS already includes everything it needs to protect itself from viruses and malware. Keep it that way with software updates from Apple. Rather than asking which non-Apple "anti-virus" or "Internet security" product is best, a much better question is "how should I protect my Mac":

Summary: Use common sense and caution when you use your Mac, just like you would in any social context. There is no product, utility, or magic talisman that can protect you from all the evils of mankind. |

Archives

November 2023

|

|

2951 Britannia crescent

Port Coquitlam BC, V3B 4V5 778-776-6222 Hours of operation Mon - Fri 9 a.m. - 6 p.m. Sat 11 a.m. - 5 p.m. (by appointment only) Sunday & Holidays - Closed |

Business Number 778569517BC0001 - © Copyright CompuBC, All Rights Reserved.

|